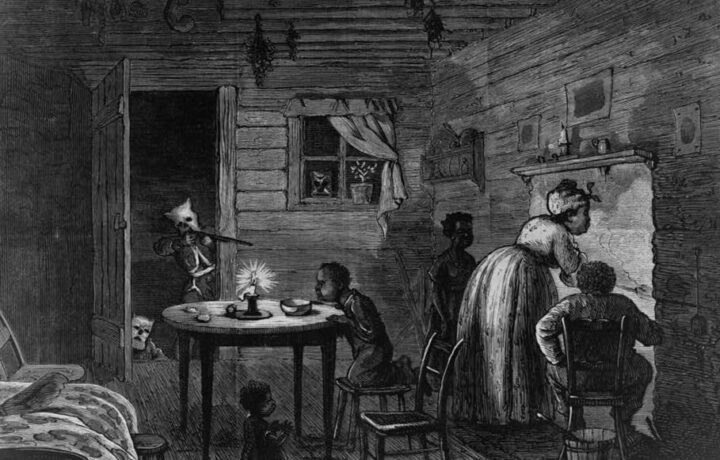

Image Credit: Bellew, Frank, Artist. Visit of the Ku-Klux / drawn by Frank Bellew. , 1872. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001695506/.

Ever since police officers in the narcotics unit of the Louisville Metro Police Department killed Breonna Taylor as she slept in her own home, I’ve been thinking about night riders in the nineteenth century, and finding disturbing parallels with SWAT and narcotics units in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Somehow these modern-day police entities are doing work similar to that of the white supremacist terrorists of a century prior, turning home spaces into the almost staged scenes of political violence. This type of violence, particularly no-knock raids, aim to scare and humiliate Black families. Koritha Mitchell calls this kind of violence against Black families, “know-your-place aggression,” which is a kind of political violence that “is a way of reminding targets of their ‘proper place,’ a way of insisting that certain people should not feel secure in claiming space.”[1]

Breonna Taylor’s is not the only high-profile murder of an innocent person killed in their own home, asleep in the middle of the night. In 2010, seven-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones slept on the couch when officer Joseph Weekley and other officers stormed into her home unannounced. Aiyana’s grandmother, Mertila Jones, reached to protect her granddaughter from intruders, while officer Weekly shot and killed Aiyana. But these raids happen more often than the pubic knows—typically not ending in death but scaring and terrorizing innocent citizens all the same. In 2014, a friend of mine woke to officers pointing rifles at her, her sons, and her barking dog. The troubling intrusion was a mistake—the harrowing result of a no-knock warrant at the wrong house. The police did not shoot that day, despite their threats to do so.

The #SayHerName report names this type of violence against Black women and their children as “collateral damage”—police claim to have accidently killed Black women and children because of their proximity to “dangerous” Black men. This type of police brutality also frames the Black family—fathers, children, infants, grandmothers, mothers, even family pets—as always already criminal.

At first glance, comparing modern day police practices to night riders and the KKK might seem extreme. Night riding was a form of vigilante violence in which groups of white men—sometimes masked with identities hidden, sometimes not—would attack Black families in their homes during the middle of the night. Night riders were avowed white supremacist terrorists, who purposefully worked outside of the law. Night riders could terrorize whole neighborhoods, kill and injure Black men and women without threat from local authorities, and even run Black families out of town if they became too economically successful or complained too much about local racism. Meanwhile, today’s narcotics units and special police teams work within the framework of the official justice system. Before they can enter a home without knocking and without warning, they must first obtain a special warrant. This requires the consent of a judge. These spaces (police units, prosecutor’s offices) are often interracial, although they may be dominated by white officers and public officials.

And yet, the comparison is productive for thinking about police violence against Black families in their own homes. Night riders purposely staged violence in African Americans homes to demonstrate their ultimate authority over the daily lives and personal property of newly freed people.[2] Under current U.S. law, and in most cases, police are legally required to announce themselves before entering a home. One large exception has been in the so-called war on drugs, where police most often target Black and brown populations. Narcotics units claim that drug traffickers are an especially dangerous subset of criminal—and their homes, friends, communities, and families are all implicated in the crime. Part of the larger narrative of the “war on drugs” is that urban Black families are failures—“broken” homes breading criminality. The war on drugs thus paints the Black home as requiring certain kinds of interventions from the state. Black homes are not worthy of sanctity or privacy.

Today, when police raids on Black families’ homes, it underscores that parents—both men and women—do not have power to protect their children from state terrorism. And many Black men still feel responsible to protect their loved ones from violence. Police officers who drag citizens from bed also enact sexualized violence, just as night riders once did. They intimidate men and women who are usually only partially clothed, frightening women and children who are asleep with the specter of sexual violence. In Breonna Taylor’s case, her boyfriend Kenneth Walker, attempted to protect her from intruders by grabbing his legally licensed gun. The police arrested Walker, and released him only after sustained protest.

Ultimately, there are a few lessons that we can take from this comparison between night riding and narcotics and SWAT units’ practices of raiding Black homes. Many activists are currently working to dismantle the carceral state—especially its role in drug enforcement. This is vital because ending the war on drugs means ending exceptions within the law that have disproportionately been applied to, and fundamentally, harmed Black people. No-knock warrants should be abolished. Police need to be held accountable when they enter homes without announcing themselves. And individual police officers, such as Joshua Jaynes in Breonna Taylor’s case, must be held accountable for lying and exaggerating on warrants for all raids. Warrants for raids must be held to a higher standard.

We must push back against white supremacist violence that has configured Black families as criminal; this has gone a long way to help justify second-class citizenship for Black communities. Cultural work, from white newspaper reports of Black criminality in the 1890s, to war-on-drugs rhetoric of the 1980s, has laid the foundation for white Americans to believe that Black families deserve racial violence. Black families have experienced “know-your-place violence” that targets Black domestic spaces specifically.

Culturally, Americans must recognize and counter long standing racial ideologies that claim that Black families are incompetent, immoral, and lazy. Any kind of racial reconciliation must include a revaluation of these cultural tropes.

LaKisha Simmons is an Associate Professor of History and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan. She is author of Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans. Follow her on Twitter @ProfLSimmons.

[1] Koritha Mitchell, “Keep Claiming Space!,” CLA Journal 58, no. 3/4 (2015): 229–44.

[2] Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South, UNC Press, 2009.; Kidada Williams, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I, NYU Press, 2012.