Image credit: Johnny Silvercloud / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)

On May 30, 2020, Governor Andrew Cuomo delivered his daily press briefing on New York’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. About nine minutes into his presentation, Cuomo expressed remorse for the horrific police murder of forty-six-year-old African American Minnesota resident George Floyd, and he acknowledged racial inequalities within the American healthcare and criminal justice systems. Cuomo rightfully commented that Floyd’s killing was not an isolated incident, but rather part of “a continuum of cases and situations that have been going on for decades.” For Cuomo, this “continuing injustice and inequality in America” primarily impacted black men, New Yorkers such as Amadou Diallo, Sean Bell, and Eric Garner. In this moment, Cuomo voiced the names of African American, African, and Caribbean black men that tragically lost their lives to homicidal police violence. Black women and girls were largely absent from Cuomo’s remarks.

Twenty-six-year-old Breonna Taylor, an award winning Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) fighting on the front lines against Covid-19, was the only woman included in the Cuomo’s list. On March 13, 2020, three plainclothes police officers, while serving a no knock warrant, fatally shot Taylor in her Louisville, Kentucky home.

And, there was another glaring omission from Cuomo’s list of police brutality victims.

The Governor did not mention any of the black women killed by New York Police Department (NYPD) officers during his father’s time as governor of New York or during his own leadership.

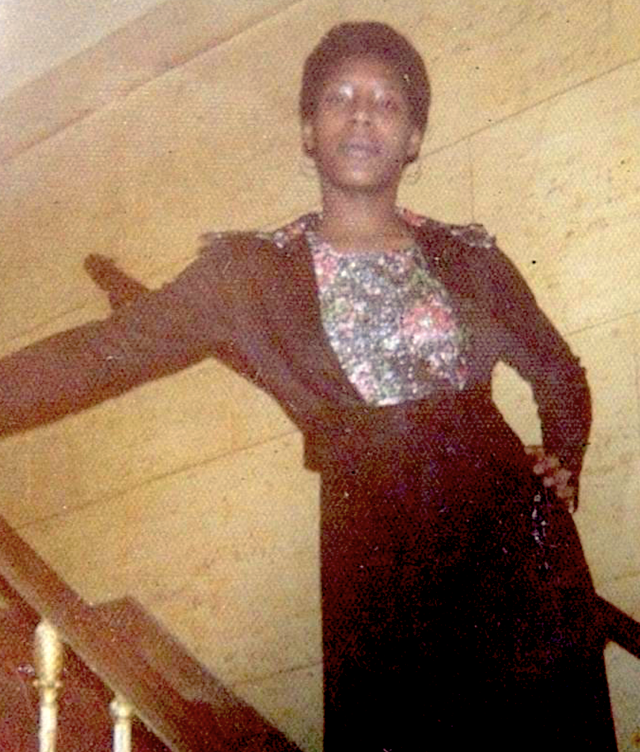

While Mario Cuomo presided over the state during the 1980s and 1990s, NYPD officers killed Eleanor Bumpurs (1984), Sharon Walker (1984), Yvonne Smallwood (1987), and Mary Mitchell (1991). In 2016, during Andrew Cuomo’s second term in office, sixty-year-old Deborah Danner was shot to death in her Bronx apartment.

Governor Cuomo’s comments on the police killings also gesture toward a more subtle form of violence against African American women. Namely, the erasure of black women, transgender, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming persons, from national conversations about policing, anti-black state violence and white supremacy. Cuomo’s sentiments also reflect the media’s failure to cover black women’s deadly encounters with police or to report on how black women experience gender-specific forms of police brutality. But the New York Governor is far from alone in his exclusionary thinking about which black bodies bear the physical, emotional, and psychological scars born of state violence.

Black women are not centered in contemporary understandings of police brutality. For instance, in an Atlanta press conference, in response to nationwide protests over the George Floyd killing, rapper Killer Mike, flanked by Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, Police Chief Erika Shields, Hip Hop artist T. I., and other city officials, tearfully told reporters that he “was tired of seeing black men [like Floyd] die.” Further, Don Lemon’s recent segment CNN broadcast, “I Can’t Breathe: Black Men Living and Dying in America,” pretty much says it all. Know this: we all want justice and we understand the spirit of the title—part of which draws on the haunting refrains of Eric Garner as NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo placed him in a fatal chokehold in 2014, and that of George Floyd as Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin who held his knee on his neck for over eight minutes. But it gives the impression that black women are not victims and survivors of state sanctioned violence. And, worse, it implies that women don’t have similar encounters with police.

African American women and girls have endured a long and painful history of police violence. And, like their male counterparts, police terror in its varying and insidious forms was—and continues to be—an occupying force in their everyday lives. From slavery to freedom, multiple forms of race, gender, and class discrimination, lack of legal protection, and denial of citizenship made women and girls prime targets for police misconduct. To borrow from historian Tera Hunter, police brutality was a broad and “chronic” phenomenon that forced women and girls to navigate the unpredictable terrain of American life in the Post-Reconstruction era. Using racist and sexist images in the turn-of-the-twentieth century, state and federal lawmakers publicly mounted derisive attacks against black women and girls, pegging them as anti-citizen, pathological and hypersexual, moral threats to American civilization. For mainstream white society, black women (especially those rigorously fighting for freedom, citizenship, and protection) were considered “problem bodies”—those bodies targeted for state intervention, surveillance, confinement, and punishment. Black women were deemed undeserving of citizenship, dignity, and protection. Horrific acts of policing became a standard and pervasive practice against women of African descent.

Everyday police violence appeared in a myriad of forms. Living, laboring, and existing outside the bounds of judicial protection, black women endured unbridled harassment and violence throughout the twentieth century. Rookie and veteran cops, detectives, police informants, and other state actors pulled their guns out on unarmed women, hurled derogatory racial epithets at women, pushed and threatened women with flashlights, batons, and chemical sprays, and brutally assaulted black women in their homes, on the streets, and while in police custody. In 1942, Alabama civil rights leader and Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) Mildred McAdory was slapped in the face, kicked in the back, and imprisoned in a cockroach-infested jail cell for several nights. McAdory was one of several detained activists that refused to identify to police the individual that removed a Jim Crow sign on a local bus. For refusing to assist police officers with minor criminal investigations and for allegedly resisting police authority, several 1970s Chicago grandmothers were dragged out of their homes and vehicles and assaulted with nightsticks.

The 1970s police killing of several women including New Yorkers Rita Lloyd and Elizabeth Mangum and Californian Eula Love, sparked outrage and mobilized fierce resistance.

Unfortunately, the pattern of unequal, violent policing endured. In April 1980, Harlem black women’s homes were ransacked during an early morning three-hour federal raid. On an alleged tip, more than fifty federal agents stormed a Harlem apartment building in hopes of capturing Black Liberation Army leader Assata Shakur, who had escaped from a New Jersey women’s prison a year earlier. Armed with machine guns and shotguns, agents broke down doors, damaged personal property, and manhandled women. Harlem resident Ebun Adelona was forced to partially strip in front of officers as they searched her skin for a scar that Shakur was “supposed to bear.”

And, in past and recent years, countless black women have died at the hands of police. In 2003, fifty-seven-year-old Harlem resident Alberta Spruill died of a heart attack shortly after police broke down her door and threw a stun grenade into her apartment. In 2014, police shot and killed Texas resident Yvette Smith after a 911 call for assistance as two male relatives fought. And unfortunately, the list of homicide killings involving black women and police continues to grow.

Even as justice continues to be denied, generations of black women activists, intellectuals, cultural producers, and victims and survivors of police violence, are drawing inspiration from the legacies and the unfinished business of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. Black women social justice leaders, writers, and intellectuals are advancing their foremothers’ political and intellectual work. Writer Andrea Ritchie, legal scholars Kimberle Crenshaw and Priscilla Ocen, and many other political activists are providing much needed public awareness and discussions on black women’s often neglected narratives. They are raising the veil on black women’s experiences with state-sanctioned violence and the criminal justice system, and they are pushing media outlets, community leaders, and the general public to broaden national conversations about policing.

All told, black women, those fighting for and demanding legal justice, protection, and respect, are challenging and inspiring all of us to #SayHerName and #TELLHERSTORY.

LaShawn Harris is an Associate Professor of History at Michigan State University and Assistant Editor for the Journal of African American History (JAAH). Harris’s scholarly essays have appeared in The Journal of African American History, Journal of Social History, Journal of Urban History, and SOULS: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society. She is the author of the multiple award-winning book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Number Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016). Follow her on Twitter @madameclair08.