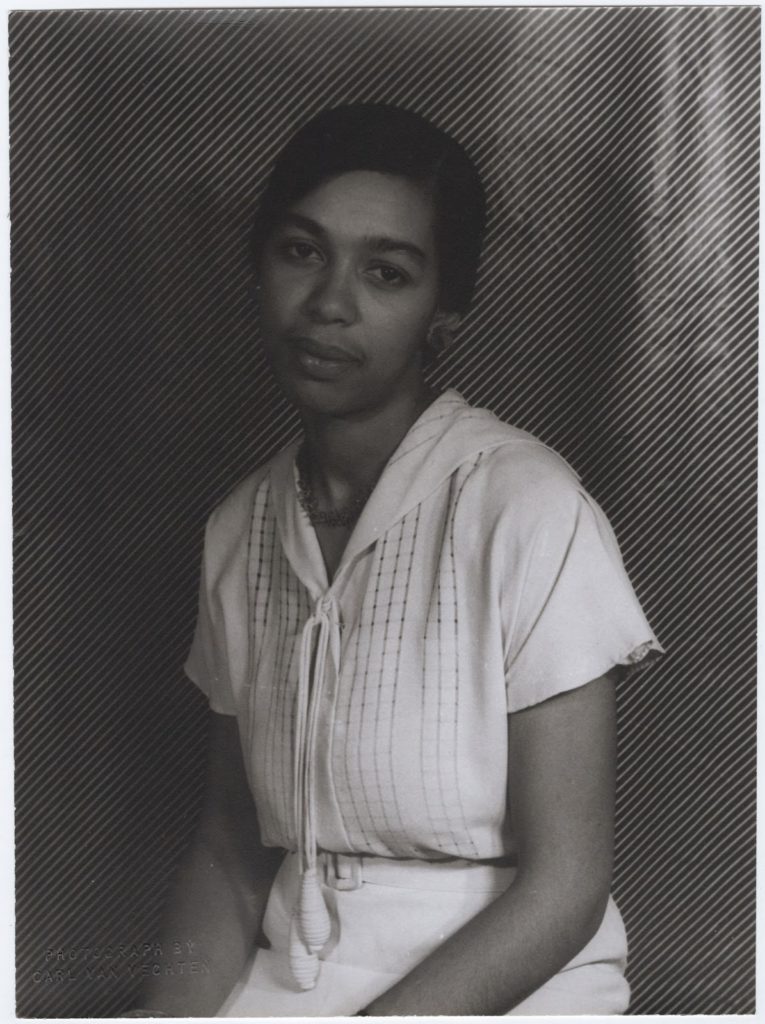

New York City’s Ethical Culture Fieldston School used a photo of an African American woman instructing one of the school’s students during the early 1930s as part of a “centennial narrative on inclusion.” Use of the image, taken by photographer Lewis Hine, gave the impression that the school had an African American teacher on staff. The teacher, Mildred Louise Johnson, was a student in their Teacher Training Department (TTD). Prior to her first student teaching assignment there, no black woman had taught at Ethical Culture or any other New York City private school. Johnson, a product of the Ethical Culture and Fieldston School from the first through the twelfth grades, was accepted into the TTD program in the spring of 1932. Johnson’s 1935 graduation from the TTD program made her the first African American to complete all divisions of the Ethical Culture Fieldston School. Absent from the use of Johnson’s image is any reference to her accomplishments. Johnson founded a summer camp in 1934 and, in the fall, founded her own private school to fulfill the second student teaching assignment required for TTD graduation. Although educated in this elite white private school, and trained as a teacher in Ethical Culture’s TTD program, she was accepted by no other private school for the final student teaching placement because school administrators were concerned about “what their parent-body might say.”

I first encountered Johnson as I arrived at the red, carved wooden doors of the school she founded at the age of twenty—The Modern School (TMS). She and her school continuously crossed my mind when I was considering education options for my daughter, but more deeply as I reconnected with grade school friends on Facebook. While I was enrolled in my last class as a doctoral student, Johnson’s work found its way into one of my assignments. In a paper, I referenced the school; my professor picked up on the reference and connected me to a scholar writing about Johnson’s father and uncle. That person tried to convince me to veer from my selected dissertation topic. I resisted, noting that there was no existing processed collection on Johnson or her school to work with. In December 2013, a former Schomburg Center colleague, Steven Fullwood, invited me to review the unprocessed collection on Johnson that had been donated to the Schomburg by Johnson’s daughter. Collection processing moves at a slow pace; this worked in my favor as I knew of only one other researcher remotely interested in the collection. As a beneficiary of Johnson’s education work, I knew that I could interpret materials contained in the collection and weave together a history befitting Johnson’s vision, drive, and accomplishments.

In 2018 I read Imani Perry’s May We Forever Stand: A History of the Negro National Anthem. Her references to Johnson’s camp and school prompted me to take advantage of the History of Education Society’s deadline extension for the 2018 conference. I decided that this was the time for me to seriously review the unprocessed collection and write about Johnson’s work. I started this work with memories of attending TMS at its 152nd Street location and with recollections of my interactions with Johnson. As I began working I knew a few things—among them, Johnson was the daughter of John Rosamond Johnson, and the niece of James Weldon Johnson; and her work began in Harlem during the Great Depression. I did not know much beyond these facts. Her contributions to Harlem, New York City, and education were a revelation. I found the prospect of this work intriguing given the school’s successful track record when juxtaposed against the long struggle that Harlem’s African American parents waged for better schooling beginning in the 1930s. Materials located thus far related to Johnson’s work confirm that this research is a necessary undertaking to bring to fruition a work that speaks to African American women’s exercise of agency on behalf of themselves and their communities in a northern setting.

TMS’s student population was majority African American. Johnson used the progressive education methods she learned in the TTD program and memories of her grade school experience as an Ethical Culture student to inform her practice. Her TMS curriculum included five core areas – language arts, social studies, science, skills, and cultural arts. Johnson produced students who were well prepared and academically on par with students at the city’s white private schools. Additionally, they exceeded the academic accomplishments of Harlem’s public school students. Her private school was the first in the city owned and operated by an African American woman. Many of Johnson’s former students went on to desegregate the very private schools where she was unable to secure a student teaching appointment during the 1930s. When it opened in 1934 Johnson’s school enrolled eight students; forty years later student enrollment exceeded 300 annually. Her work at the school and camp is documented in local and national newspapers; a researcher simply needs to know how to find her, the camp, and TMS in these publications.

Johnson lent her talent to numerous organizations outside of TMS that contributed to the improvement of lives in the Harlem community and New York City at large. One example is her work was establishing a nursery school to alleviate the shortage of nursery programs in Harlem. She worked with pediatrician Dr. Thomas W. Patrick; nursery school expert and progressive education advocate Jessie Stanton; and socialite and philanthropist Dorothy H. Paley, to open the Neighborhood Day Nursery School on November 7, 1943.2 Johnson served on its first board of directors; as well as boards for other local education institutions and social service agencies. She also regularly worked with local higher education institutions to study the needs of Harlem’s children.

In trying to uncover the life of Mildred Johnson and the history of TMS, the collection at the Schomburg Center is key. It contains several written accounts of recollections and reflections on her life, the camp, and TMS. The work of a historian in instances where the subject is not well known to the history community is to corroborate the subject’s recollections and document events that place the subject in historical context. To do this I had to find Johnson and TMS in other archival collections – through family members, her social network – and publications. Additional sources include people who remember her, the school, and her community work. This work is not only a recovery of her accomplishments but also presents a model of educational success for northern African American students that spanned more than half of the twentieth century. Because of the prominence of her father and uncle, a search of their respective collections provides critical information on her work at TMS, the camp, and her personal life. Additionally, two other collections at the Schomburg Center yielded information on Johnson, as do collections of material at the Warwick Historical Society, another at the New York Historical Society, and a collection at UMass Amherst that contains correspondence with W. E. B. Du Bois.

While I have been able to find Mildred in several places, there is still a void in the available materials that prevents a more complete telling of her life story and work. As a graduate of Johnson’s grade school, I, along with fellow alumni, teachers, and parents know of her work, as do members of the Harlem community. The first-round review of my pending article included queries from the reviewers asking why Johnson and her work are unknown to historians. This feedback struck me as odd given that at some point every historical event or subject was unknown. From my perspective, it is a matter of where we look for historical actors and events. In the case of my dissertation, I challenged a commonly accepted narrative on the student-led sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina. For this work, primary sources existed in my personal archive, located in a memory book my mother saved from my grade school and high school years. TMS existed for sixty-five years in Harlem. I know that Johnson and the school existed and left a lasting impact on the community and that there are graduates, parents, and professionals involved in schooling and social services who recall Johnson and her TMS work. I continue to search for more information on Mildred Johnson to bring her life and work to the attention of researchers interested in history related to New York City, Harlem, urban education, and northern African American women educators.

Dr. Deidre B. Flowers earned her PhD from Columbia University in 2017. Her work centers on black women in education. Dr. Flowers’ research interests include women in education, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, women’s higher education, higher education leadership, and student protest and activism. Her dissertation, “Education in Action: The Work of Bennett College for Women 1930 – 1960,” argues that Bennett College intentionally sought to educate socially conscious and civically engaged citizens during the twentieth century who worked to improve African Americans’ quality of life domestically and abroad. Also a graduate of Hampton University and Syracuse University, Dr. Flowers is a life long resident of Harlem.