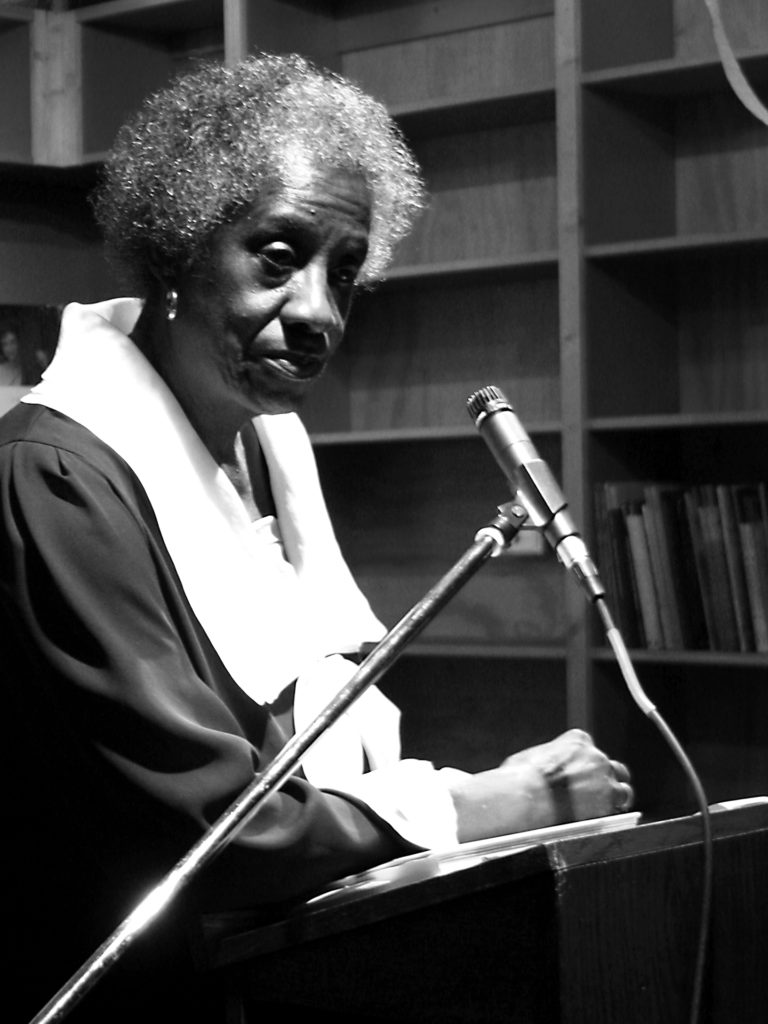

Unita Blackwell first traveled to China in 1973 with Shirley MacLaine in a delegation of women to record the documentary The Other Half of the Sky. Based on a quote by Chairman Mao Zedong concerning gender equality in China, the film intended to understand and record the lives of women in Communist China. Born into a sharecropping family in rural Mississippi in 1933, by the time of this initial trip, Unita had been reborn as a freedom fighter. Unita’s conversion took place in the summer of 1963 when Civil Rights workers came to her then-hometown of Mayersville, Mississippi. That summer ignited a passion for social justice that shaped her first trip to China. Her passion and dedication to social justice compelled her to establish the U.S.-China Peoples Friendship Association (USCPFA) in 1974, an organization instrumental to the U.S.-China bilateral relations.

U.S.-China bilateral relations has been a major area of focus considering ongoing trade talks between the two nations. As we ponder the future of U.S.-China relations, it is important to examine its history, including the impact of both state actors and individuals. One particularly influential group that comes to mind is China Hands. Although the term was originally used to denote nineteenth-century merchants in Chinese treaty port cities, it has, over time, been redefined to refer to individuals deemed experts on China. This designation denoting expertise has not been one bestowed to African Americans who also were experts on and had an impact on modern U.S.-China relations. An expansion of the term China Hands to include Black internationalism encompasses how Sino-African American relations impacted U.S.-China relations. I frame individuals such as Unita Blackwell as China Hands to encompass the role of Black internationalism in shaping modern U.S.-China relations and to call for the de-centering of Whiteness in Chinese foreign relations history.

Vanita Reddy in “Affect, Aesthetics, and Afro-Asian Studies” highlights the need for a new framework to evaluate the archive, scholarship, and aesthetics of Afro-Asian studies. According to Reddy, “recent work in Afro-Asian studies has tended to reproduce a heteromasculinist genealogy of cross-racial alliance…Yet perhaps because it relies so heavily on public intellectualism, direct action, and armed militancy as expressions of cross-racial radicalism within the historical record, this body of work reveals an almost exclusive focus on men as political and historical actors in the construction of Afro-Asian solidarities” (p. 290). As a result, the Afro-Asian archive and related scholarship reproduces “a heteronormative and male-centered genealogy of Afro-Asian alliance” (p. 291). For example, seminal photographs commonly associated with Afro-Asia, such as meetings and exchanges between W. E. B. Du Bois and Mao Zedong, inadvertently shape this space of cross-racial exchanges as a heteromasculinist boys club. Reddy argues for a queer feminist reevaluation, specifically as it relates to affect and aesthetics, within Afro-Asian scholarship to “inquire into what kinds of political affiliation—and even what notion of the political—might emerge” (p. 289). I take Reddy’s critiques of Afro-Asian scholarship as a point of departure for my own research regarding Sino-Black relations in Maoist China, specifically as it relates to locating Black female voices within this Black Internationalist space due to the triple silencing and erasure of them in the traditional archive along the identity vectors of race, gender, and class. While the recent scholarship of Robeson Taj Frazier, Dayo Gore, Yunxiang Gao, Barbara Ransby, Gerald Horne, and others has highlighted the experiences and travels of Victoria “Vicki” Garvin, Shirley Graham Du Bois, and Eslanda Robeson in Maoist China, locating the subaltern voices of other Black women instrumental to Sino-Black relations, such as Mabel Williams, is an ongoing challenge. Recently, however, the location of information concerning Unita Blackwell and her lasting impact on Sino-Black relations and U.S.-China relations has replenished hope and the drive to continue to research the role and impact of Black female labor regarding Sino-Black relations.

At the time Unita Blackwell established the USCPFA in 1974, U.S.-China bilateral relations were young, making it a precarious and sometimes tenuous time for and between the two nations. To assist the American public’s perception of Communist China, Blackwell “conceived of the idea of engaging in person-to-person diplomacy as a means of improving mutual understanding and strengthening the bonds of friendship between the nations” (U.S.-China Peoples Friendship Association Photograph Collection). Additionally, the USCPFA also disseminated information through many means, including their quarterly publication US-China Review, public outreach initiatives such as Chinese language courses, workshops and, most notably, access to China via guided tours. At the time of its founding in 1974, the USCPFA was a pioneer in “organizing tours of China, and for several years they were virtually the only option for American citizens to visit the People’s Republic” (U.S.-China Peoples Friendship Association Photograph Collection). The services and outreach initiatives of the USCPFA under Blackwell’s leadership offered the average American information about and access to China. Blackwell founded, presided over (between 1979 and 1983) and actively served on the board of the USCPFA. The four years of her presidency saw diverse outreach efforts. As the face of the organization, she organized China tours for Black public officials, traveled to Tibet in 1980, assisted in the hosting of Chinese delegations to the United States in the early years of modern U.S.-China relations, and even created the symbol of interlocking flags that continues the symbolize U.S.-China relations (Morris, 14). Unita Blackwell is a China Hand as USCPFA spearheaded initiatives that helped foster amicable relations between the United States and China during an uncertain time in modern bilateral relations. Additionally, her commitment to social activism is evident in her efforts to provide access to anyone interested in learning more about Communist China. The ability to learn and study Chinese was expanded, and area studies or Chinese history was no longer accessible only at an institution seminal in the establishment of Chinese studies. While Blackwell played a pivotal role in U.S.-China relations at a critical historical and political juncture, denoting her work and expertise through designating her as a China Hand is not common practice. Throughout her life, Blackwell had traveled to China an impressive eighteen times. Her performativity of Blackness shaped ideas of race and gender in China, and her efforts through USCPFA demystified the enigma known as Communist China. Although we lost Blackwell in 2019, she created a legacy through the work she began. Through a de-centering of Whiteness and an expansion of the archive, Blackwell’s labor and activism illuminates Black women’s internationalism in Asia.

Keisha A. Brown is an Assistant Professor of history at Tennessee State University in the Department of History, Political Science, Geography, and Africana Studies. Dr. Brown was a 2018–2019 postdoctoral fellow at the James Weldon Johnson Institute at Emory University and is a Cohort VI PIP Fellow with the National Committee on US-China Relations. As an Asian studies scholar, her research of Sino-Black relations examines networks of difference in China used to understand the Black foreign other. Dr. Brown’s research and teaching interests include comparative East Asian histories, postcolonial theory, transnational studies, world history, and race and ethnic studies.