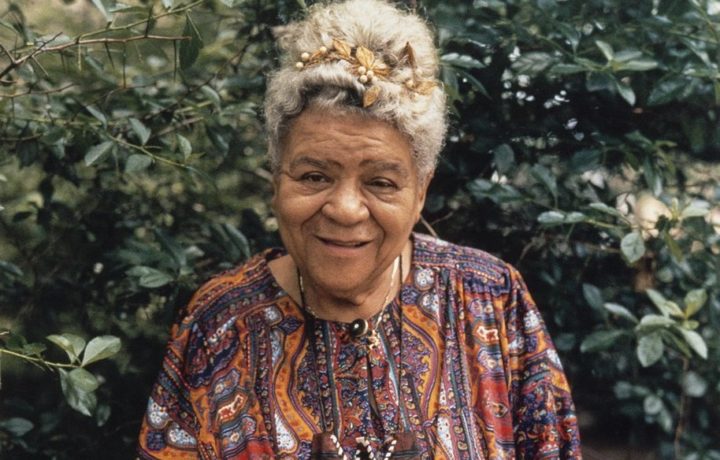

Spiderwebs are curious things. They are everywhere, but often invisible to the naked eye. If fact, many of us don’t even register them until the light hits the strands of the web just right. Only then do we recognize the intricate pattern of the web or the way it connects or bridges structures. This is how most people encounter renown black activist “Queen Mother” Audley Moore. One of the twentieth century’s most prominent and prolific activist-intellectuals, she was ever present, her ideas and activism forming key infrastructure of the twentieth century Black Freedom Movement. Yet, researchers usually happen upon her by accident—their research of another subject ends up shining a light on Moore’s activism.

Audley Moore’s political life spanned the 1920s to the 1990s, during which time she was a part of most major black movement moments and organizations ranging from the UNIA to the Million Man March. Moore’s political life began when she became a black nationalist and a Garveyite. She rose to activist fame as a Communist Party organizer in the 1930s and 1940s. By the 1960s, she was revered as a “Queen Mother” of the movement, introducing the Black Power generation to nationalist principles and jumpstarting the modern reparations movement. She remained a staunch advocate of black nationalism, Pan-Africanism, and reparations until her death in 1997.

Despite her prominence, she does not have a central archival repository and is largely invisible in the traditional historical archive. This is due, in part, to that fact that she only had an elementary school education. Lacking access to “formal” or “traditional” modes of expression, Moore mostly transmitted her ideas orally, leaving few written records of her ideas. As a working-class black woman, she was not the subject of much study or documentation while she was alive, making remaining records of her activism sparse. The task for historians then, is to carefully shine the light on Moore’s web, revealing how she spun many of the ideological and organizational strands that held the Black Freedom Movement together.

One approach to recovering Moore is to look for the points where the movement’s silk strands met. This means mining the archive for moments in time where multiple actors’ ideas and causes overlapped through a protest, a monthly meeting, or even a workshop. Here one might find a meeting roster, a working-group manifesto, or a position paper authored by a collective or headlined by other, more visible activists. When researching Moore, such documents might also be overlooked because there was no indication that she was a part of the group or protest. Yet, more careful examination might reveal Moore’s name listed as part of those attendance because of her shared beliefs or values. A slip of paper among many, such an artifact is unlikely to be listed in finding aid or flagged as a reference to Moore. Yet, by searching for the spaces where multiple movement strands came together, even for a brief moment, researchers can reconstruct Audley Moore’s activities and ideas, revealing how she helped construct and reinforce its webbing.

Another approach is to focus the light on the web rather than the weaver. Queen Mother Moore was not just notable for her own activism, but also for the ways in which she politicized and empowered others. By the 1960s, she became the literal and ideological connection between the Old Left and Black Power organizers, ensuring that a new generation understood the ideological tenets of nationalism and communism and instilling in them the importance of quotidian acts of struggle. Documenting this ideological influence requires one to take a step back and look at her activist relationships rather

than focusing on Moore’s actions alone. This includes examining the archives of groups and activists outside of Moore’s known associations and contemporaries to find instances in which she might have served as an informal mentor or advisor rather than as the leader of a group. Looking for these expressions of intellectual influence rather than pro-typical evidence of “intellect” or “leadership” reveals a complex web of sustained intellectual engagement among black radical women like Moore.

Ultimately, Queen Mother Moore prompts us to think about what new frameworks can be developed for uncovering the histories of twentieth-century black women activist-intellectuals who do not have a traditional archive. Conceptualizing Moore as a weaver of an intricate web of movement activism and intellectualism is one approach. For nearly seventy years, Queen Mother Audley Moore moved in and out of spaces spinning together a masterful web of people, ideas, events, and organizations that created the infrastructure of the Black Freedom Movement. Her non-traditional life makes her hard to track, but also reveals an incredible history when the light hits her web just right.

Ashley D. Farmer is Assistant Professor of African & African Diaspora Studies and History at the University of Texas-Austin. she is the author of Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era,a co-editor of New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition, and the co-curator of the Black Power Series. She is also the author of the forthcoming biography, Queen Mother Moore: Mother of Black Nationalism.Follow her on Twitter @drashleyfarmer.