Three and a half years have passed since Rihanna released an album despite fans, affectionately known as the Rihanna Navy, clamoring for new music from the Bajan pop music star. But there’s been no shortage of Rihanna’s presence, influence, and cultural impact amid the demands for a ninth studio album. From her award-winning and best-selling collaboration with Puma to her racially and ethnically inclusive, consumer friendly makeup brand Fenty Beauty to her body-positive, sexy lingerie line Savage X Fenty, Rihanna upped the ante on her status as a style icon to make waves in the fashion and beauty industries.

Her latest endeavor as the first black woman to lead a major fashion luxury house, eponymously named Fenty, is perhaps one of the most history-making moments of her storied career. Launched on May 29 in Paris, the high-end, LVMH backed brand immediately disrupted the still- predominantly-white luxury fashion world. Although she was unaware of her pioneering achievement as a black woman in the high-end fashion industry until months into developing Fenty, Rihanna dug into the archives of modern Black cultural expressivity for inspiration and guidance. The result is a brand deeply indebted to black artists, models, tastemakers, photographers, writers, and designers of the last several decades from throughout the African diaspora.

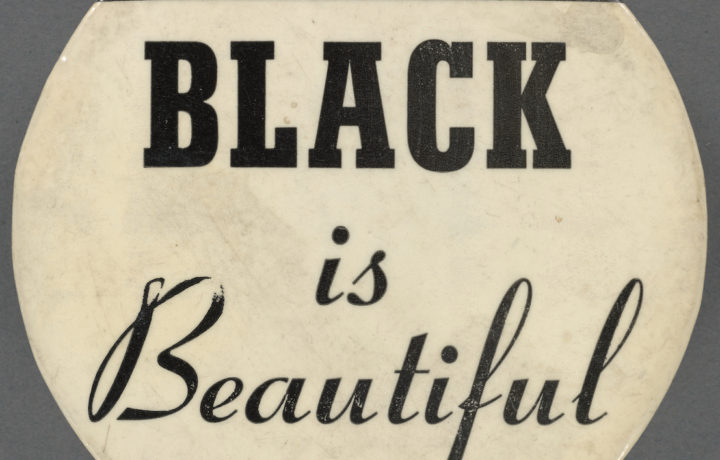

The homepage for Fenty features a Kwame Brathwaite photograph of an underground fashion show held on Marcus Garvey Day by the 1960s Harlem-based collective of Black artists, the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS). A force in the popularization of the “Black Is Beautiful” cultural movement, Brathwaite and his fellow AJASS members helped to shape a distinct, African diasporic–centered cultural and sartorial milieu within the Black Power movement. The photograph, which Rihanna also posted on Instagram with the caption “Kwame Brathwaite. archive” captures three black, stylishly coiffed models, an equally dapper band, and a white banner with the words Buy Black prominently displayed. The selection of this image for the homepage, one that unapologetically centers blackness, is intriguing because it provides an alluring peak into the Black is Beautiful movement and introduces the world to Rihanna’s distinct design point of view and brand articulation.

For Rihanna, the archive of black style was ripe for exploring. It’s not simply the aesthetic captured by Brathwaite’s photography that captivated and inspired the pop star turned mogul. It’s all of the elements extant in such an image that prompted Rihanna to take a deep dive into an era of Black style and politics as a guiding force for crafting her luxury brand. Her excavation included reading the work of historian and cultural critic Tanisha Ford. In her co-authored book Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful and in previous work, Ford documents both the history and significance of Brathwaite, his brother Elombe Brath, the AJASS, and the Grandassa Models. Inextricably connected to a black nationalist political ethos and influenced by Garveyism and other pan-Africanist political movements, these Harlemites challenged white cultural hegemony while cultivating a pro-black creative standpoint.

Rihanna’s use of historical signifiers and artifacts of a cultural movement that explicitly rejected white beauty ideals and reveled in the beauty of black women is quite noteworthy. While Fenty may be out of reach for the average consumer, its messaging and nostalgic take on such a rich black cultural movement are widely accessible. Whether helping spark renewed interest in Brathwaite or the troupe of deep and dark brown–skinned, afro-sporting women who were Grandassa Models, Fenty provides a conduit to cultural-historical inquiry. Those purchasing from Fenty are buying black and contributing to an aesthetic and sartorial legacy in which black women are central.

Rihanna also connected with Brathwaite as a fellow Bajan-American creative living in the United States, although she recently moved to London as she spent time developing her new brand. Black Is Beautiful connected the routes and roots of the African diaspora: from the incorporation of prints and fabrics from countries throughout Africa to the sewing and tailoring labor of black women in the United States designing the clothes featured in Brathwaite’s photos and worn at other AJASS events. The blackintimated in both Buy Black and Black Is Beautiful is multi-ethnic, multi-national, and expansive in its cultural resonance. It is unsurprising that Rihanna, a first-generation Caribbean-American black woman would identify Brathwaite and Grandassa Models as muses for her collection.

The decision to formally introduce the world to Fenty via photographs from an archive filled with images and ephemera from a black cultural movement is compelling. It immediately confronts a history of racial exclusion within the fashion industry while highlighting how black people have always produced black-centered cultural spaces. Although Rihanna’s line targets all races of potential buyers, her citation and inclusion of Brathwaite, the Grandassa Models, and the broader Black Is Beautiful movement are overt gestures toward the role of black cultural history in shaping fashionable black futures.

Treva B. Lindsey is an Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The Ohio State University. Her first book is Colored No More: Reinventing Black Womanhood in Washington D.Cis a Choice 2017 “Outstanding Academic Title.” She is currently working on her next book project tentatively titled, Hear The Screams: Black Women, Violence, and The Struggle for Justice. Follow her on Twitter at @divafeminist.