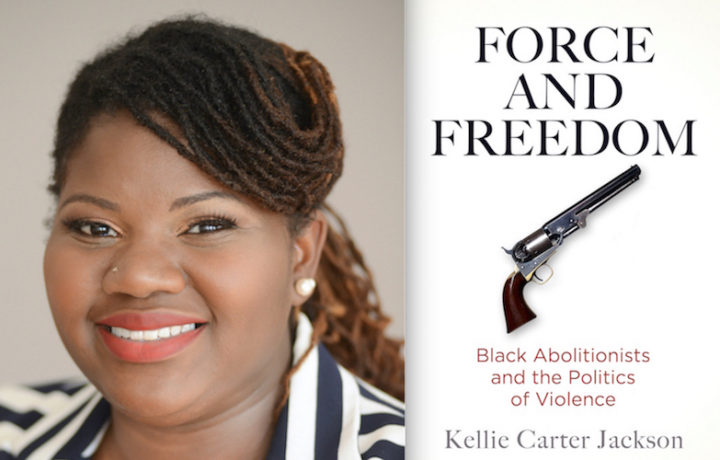

This month I had the opportunity to interview Kellie Carter Jackson about her new book, Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019). Dr. Carter Jackson is a 19th century historian in the Department of Africana Studies at Wellesley College. Her research focuses on slavery and the abolitionists, violence as a political discourse, historical film, and black women’s history. Dr. Carter Jackson is also co-editor of Reconsidering Roots: Race, Politics, & Memory (Athens: University of Georgia Press). Her essays have been featured in The Atlantic, Transition Magazine, The Conversation, Boston’s NPR Blog Cognoscenti, AAIHS’s Black Perspectives, and Quartz, where her article was named one of the top 13 essays of 2014. She has also been interviewed for the New York Times, PBS, Al Jazeera International, Slate, The Telegraph, Reader’s Digest, CBC, and Radio One. Follow her on Twitter @kcarterjackson

Kali Nicole Gross (KNG): A mentor once told me that we do not choose our projects; rather, the projects choose us. With this in mind, please tell us what led you to this topic.

Kellie Carter Jackson (KCJ): I first became interested in this project as an undergraduate at Howard University. I wrote a paper on the radical abolitionist John Brown and wondered what possessed a white man to want to take up arms in defense of black people. After spending time in the archives at Moorland-Spingarn, I realized that Brown was not really a leader but rather a follower of black revolutionary violence. John Brown was merely putting black ideals and ideology into practice. To me, black ideals regarding political violence was a story that needed to be told.

KNG: How you are defining violence, and why is it important for us to know that black abolitionists embraced it? Please also explain how you used historical sources to find and center their voices.

KCJ: Force and Freedom could just as easily be expressed as force for freedom. The paradox of using force and violence to bring about freedom and ensure peace is common within our own Western political context. Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” is the quintessential ultimatum. I see violence for black abolitionists as a political language, meaning violence became a way of communicating and provoking political and social change, particularly without the ballot. I think understanding political violence is often about understanding an ideology of last resorts. In many ways, this study is an analysis of “last resorts” among black Americans. It asks: Should the enslaved or free black people be forced to obey laws that do not grant them the rights to shape such laws? The era of revolutions set an early example for understanding violence as both a rhetorical and a physical weapon to maintain the status quo, as well as the model to overthrow it.

We can’t forget that slavery was created in violence. Slavery was sustained through violence. It seemed logical that slavery might only be overthrown through violence. I think not talking about or centering the embrace of force by black abolitionists is somewhat dishonest. It can make the Civil War seem like a spontaneous and unfortunate outcome. But human bondage is warfare. The enslaved have been at war since they were placed in bondage. I flush out these ideas by highlighting the speeches, writings, and actions of black abolitionists. I centralize them as both founders and foot soldiers in their quest to bring about freedom and equality.

KNG: I was really interested in your decision to push past reading violence as masculine and to read black female abolitionists’ support of armed resistance together within broader shifts in the movement. Could you talk about these methodological decisions?

KCJ: More often than reported, black women employed similar motivations for force as their male counterparts. Throughout the 1850s, the political climate gave rise to black women’s need to address their grievances. Women such as Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Mary Ellen Pleasant, Maria Stewart, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Sarah Remond, Harriet Purvis, and Sojourner Truth assumed stronger stances in the aid of fugitive slaves and self-defense. It is well recorded that Harriet Tubman and other women were not above packing a pistol for their journeys out of bondage. Black women warned their communities about kidnappers, confronted slave catchers with guns, and corroborated on collective and protective violence. Within my work, it was important for me not to segregate women’s roles in the movement. Black men and women collectively resisted oppression. Self-defense is not gendered. Black women had every reason to contemplate or resort to violence as a meaningful tool to combat their powerlessness.

Frederick Douglass once said, “when the true history of the anti-slavery cause shall be written, woman will occupy a large space in its pages; for the cause of the slavery has been peculiarly woman’s cause.” I could not agree more.

KNG: Please expand on one or two of the personal experiences that changed individual black abolitionists’ political views on violence.

KCJ: There are so many great stories that moved black leaders to take on a more forceful stance, but the Fugitive Slave Law was by far the greatest accelerator. The law threatened fugitives and free black people. The law pushed two options: fight or flight. Martin Delany supported emigration, but in contempt for the Fugitive Slave Law, he declared: “If an officer searching for fugitives crosses the threshold of my door, and I do not lay him a lifeless corpse at my feet, I hope the grave may refuse my body a resting place, and the righteous Heaven my spirit a home.”

The caning of white abolitionist and senator Charles Sumner by Preston Brooks in the senate chamber made national headlines. In my book, I talk about a fifty-year-old black woman by the name of Amelia Robinson who was outraged by the beating. She wrote to her local newspaper and called Brooks a coward for beating an unarmed man. She challenged him to meet her any place with “pistols, rifles, or cowhides.” She claimed that she was anxious to do her country some service either by “whipping or choking the cowardly ruffian.” These stories give me life! It was constantly made clear that these were not empty threats.

KNG: You beautifully recount the turmoil and rage of black abolitionists, especially in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Law and the Dred Scott decision. I was surprised by slogans such as “hands off or death.” Please tell us a little more about how this legislation impacted their movement. In what ways did it reposition black abolitionists with respect to their white abolitionist counterparts?

KCJ: By the 1850s, the abolitionist movement had been advocating for emancipation for over twenty years with little to no progress. Virtually every piece of legislation put forth during the antebellum period favored slaveholders. The Fugitive Slave law put fugitives at risk, but the Dred Scott Decision made clear that even free black Americans had no rights; they weren’t even citizens. The defeats of the 1850s gave rise to black militancy and fueled forceful and even violent backlashes from the black community. While Canada became the only haven among black people, more black leaders were invested in fighting over fleeing. Black leadership did not just warn others of war, they welcomed it. The militancy of black leadership compelled white leaders to get aboard. John Brown was a perfect example of the acceleration of violence regarding sectional tensions both in “Bleeding Kansas” and Harpers Ferry. In 1859, a radical abolitionist newspaper, the Anglo-African Magazine, declared, “So, people of the South, people of the North! Men and brethren, choose ye which method of emancipation you prefer—Nat Turner or John Brown’s.” The options black abolitionists presented back to the American public left little choice in how exactly slavery would be abolished.

KNG: In chapter four, you ask a powerful question that I would like you to answer here: What might it do to envision Brown not as a leader of a single, anomalous event but as a follower of black revolutionary violence who put this tradition into practice? Please share your insights on what we and history gain.

KCJ: John Brown was not just a follower but also a fan of black revolutionary leaders. He read as much as he could about Haiti and Toussaint Louverture. He sought out the help of Lewis Hayden, Harriet Tubman, and Frederick Douglass. The greatest financial supporter of Brown was a black woman named Mary Ellen Pleasant. She donated $30,000 to his efforts. Without the contributions of black radicals, Brown’s efforts were stillborn. One cannot divorce Brown from the ideals and practices of African Americans both during the raid and long before the raid was conceived. Much of my work is about placing black abolitionists at the center of their own movement. I borrow from the late historian Stephanie Camp, to note that black narratives not only add to our understanding of history but change what we know and how we know it.

KNG: As your book is about to be released, what are you most proud of and what, if anything, do you expect will be controversial for readers?

KCJ: Too much of the abolitionist movement is told through the lens of sympathetic white allies or limited to the narratives of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. There are so many black leaders who accomplished incredible feats in the face of insurmountable odds. At the very least, I want readers to be exposed to something new and equally important; I want readers to be affirmed in what they may already know: black abolitionists efforts were central to the abolition of slavery. The call for “Freedom Now” was never more urgent than in the nineteenth century. I hope readers can connect abolitionist activism to a long tradition of resistance to oppression in American history. I’m proud that alternative voices will finally have some volume and, in turn, historical value for their efforts.

As for controversy, I think violence is always a tough pill to swallow. There is a tendency to privilege the performance of nonviolence in this country. We talk about the Underground Railroad solely in terms of heroic acts of escape; but fleeing often required fighting. One of the perennial questions in political thought asks: Is violence a valid means of producing social change? Force and Freedom addresses how black abolitionists answered this question. A retreat from engaging in a complex understanding of the political purposes of violence limits both how we see and make use of the past. Through the force of events, Frederick Douglass once said, “The American public … discovered and accepted more truth in our four years of Civil War than they learned in forty years of peace.” The truth held in violence is an uncomfortable but invaluable lesson.